How to manage a rewrap under MacOsX using free software

Sometimes it takes very little to make your life easier, but it takes even less to complicate it… When working with several cameras and dslr’s that use the AVCHD structure you can have some problems managing them from editing and post programs, because they use the MTS format as the container, and a series of folders and subfolders as the structure. It all originated from the idea of recording this way, because it is also the format used to create a bluray, so copying the complete structure inside a bluray disc will then be read by a regular player. All well and good if we want to make a bluray right away, but if we want to edit them … both under windows and under mac we may encounter difficulties.

Under MacOs X the AVCHD structures are seen as a more … “rigid” structure so it is important to know how to handle them.

The avchd is an H264 file encompassed in a structure of folders and subfolders that are useful and parallel to those of the bluray to simplify the transition from the camera to the bluray disc with a simple burner, but when we want to edit the files we are faced with files with .MTS extensions, which the finder does not handle comfortably (actually neither does the windows explorer).

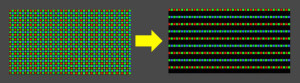

The easiest, fastest and most convenient operation to handle them is the process called ReWrap, that is, we change the container, from Mts to mov. ReWrap does NOT recompress the data, so there is NO alteration or loss of information. But by changing the container to mov magically all programs will open the files, the finder will preview them for you, and so on…

Also the operation is little slower than copying the files.

There are several applications that perform rewrap, and in particular the most powerful one is Ffmpeg, a free utility that performs hundreds of tasks, with speed, quality, etc. too bad it is a line command program, that is, it is run from the command console as was done 40 years ago, fortunately several developers have created graphical interfaces to perform this task.

I point you to two software programs that use ffmpeg under mac, which allow you to rewrap. Below you will find directions for using the first one free, and the link for the second one which is paid, although a very trivial amount.

What are the steps to take?

Few and simple :

Step 1 : being able to read the structure files as a file and not as a folder

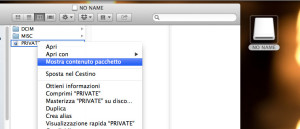

To copy the AVCHD stream files we need to see its folder, so we open the related tab :

The Private folder looks like a file, but it really only takes a little, with a right click we choose :

SHOW PACKAGE CONTENTS

So we can navigate the internal folders, we will have to repeat this operation for several folders to navigate the subfolders.

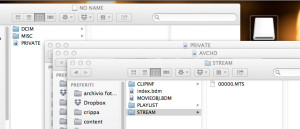

We need to go inside the structure of the AVCHD

Basically we have to get inside :

– PRIVATE – AVCHD – STREAM

In this very last folder we find the Video files.

Let’s copy them to the ‘Hard disk to be faster in the various procedures.

It is also possible not to copy them directly to the disk, but it would be slower operation

Stage 2 Media Converter

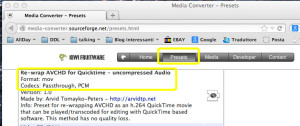

Let’s go to the site of Media converter, a Free utility that acts as a Front END to free ffmpeg encoder.

From the Presets section, download the preset for AVCHD rewrap, because it is not standard in the program.

There are two, one that doesn’t consider audio, the other that does.

The program requires no installation

just copy it to the application folder and run it.

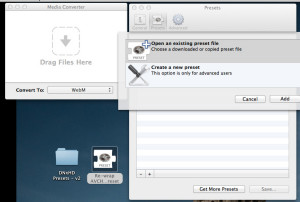

To install presets just go to preference, and click on the preset item.

To add the preset just click on the symbol in the lower left corner

The little window you see below will open, and click on Open an existing preset file, and select the downloaded file.

Once you have loaded the presets of your choice, you can close the preference panel. And you are ready to perform the ReWrap.

Step 3 CONVERSION

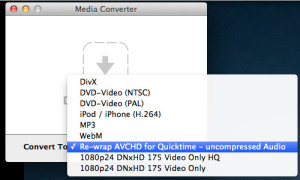

We choose from the drop-down menu the format we want as the final output for our files, in this case we choose Re-Wrap.

We drag the video files we want to handle directly onto the program window.

As soon as you release them the program asks where to save the resulting files, you specify a path, and the program starts working.

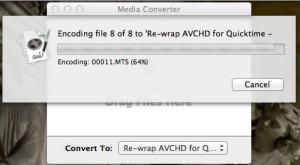

And then you only need to wait a few seconds or minutes depending on the number and duration of the movies.

The result will be .MOV files that can be opened and managed in various programs.

Side note, if for some reason it does not make you install the preset for all users, the reason is very simple, you do not have permission to update the internal folders as a user, so you will have to download the free utility BatChMode, which allows you to reset the permissions of the preset folder of the program.

An alternative is to manually copy into the user/user name/library/application support/media converter/Preset folder the preset files that you can find online.

Another very interesting application for rewrapping under MacOsx is the Emmgunn suite, a series of utilities that allow you to either rewrap a file to mp4/mkv/avi or compress it to those formats if the source codec is not supported in the rewrap. The free version has the limitation of doing one conversion at a time, but enough to appreciate the quality of interface etc. Also based on Ffmpeg, it is an encoder suite that costs less than a pizza and is worth it for speed and quality.

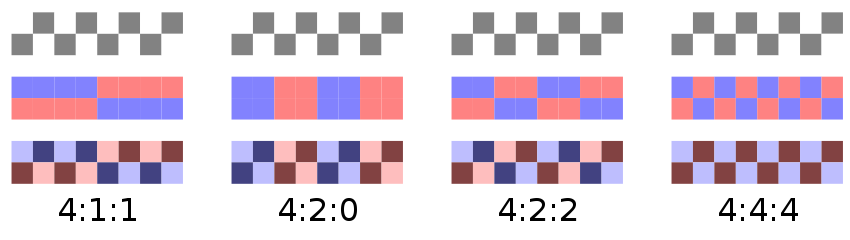

Update July 21, 2018: thanks to the gradual development of software vendor’s stinginess (I am being caustic today and I have reason to be) most video software no longer reads/decodes audio in AC3 codec because the Royalties with Dolby have expired and have not been renewed, Windows with the 1851 upgrade has removed support for that codec from the system so you may find that your files are without audio (most prosumer cameras and cameras use dolby AC3 for audio encoding). The preset that rewraps the video converts the audio to uncompressed and then allows you to then read it even from applications without AC3 codecs

In the last few months I am discovering a flood of small products, shorts, mediums and feature films made by fanfilms, that is fans of one or the other character of cinema, TV, comics.

In the last few months I am discovering a flood of small products, shorts, mediums and feature films made by fanfilms, that is fans of one or the other character of cinema, TV, comics.